What's a number?

OK, so a bit of a silly question. Of course, we all know what numbers are. But humor me, and try to define a number without using “number”, “quantity”, or anything that refers back to a number itself.

But, before we learn numbers, we have to first understand something simpler: counting. Couldn’t we define numbers in terms of counting? Well, yes, otherwise I wouldn’t be writing this article.

Now, to not end up with a forty page book, I’m only going to go over how to define the whole numbers (I’m going to ignore negative integers, fractions, \(\pi\), etc.)

Basically, a mathematician named Peano had a similar idea back in the 1800s. Back then, even mathematicians didn’t really know what numbers were. Some of them felt that they were simple enough that they didn’t need a definition. On the other hand, some mathematicians liked thinking about numbers in terms of geometry. Like if I draw one line, that’s 1. If I draw another line 2 times as long next to it, that’s 2, etc. It works, but it’s a bit annoying to have to work with geometry all the time. Unless you like drawing, which a lot of people go into math to avoid.

Anyway, back to Peano. During the 1800s, mathematicians were starting to ask some weirdly difficult questions. Like, how do we know that \(a + b = b + a\)? How do we even know that \(2 + 2 = 4\)? How do we even know that \(4\) exists?

Well, we need to start somewhere, and Peano decided we needed a few basic Laws Of Mathematics for numbers (mathematicians like the word axiom). These are rules that are considered self-evident.

He came up with a total of 9. In advanced 21st century mathematics, there are generally considered to be 5. (No, it didn’t turn out that \(9 = 5\). 4 of the axioms are really part of logic. Stuff like if \(a = b\), \(b = a\). In the 19th century, they didn’t really distinguish logic from math, but now we do.)

Anyway, let’s go through the Laws!

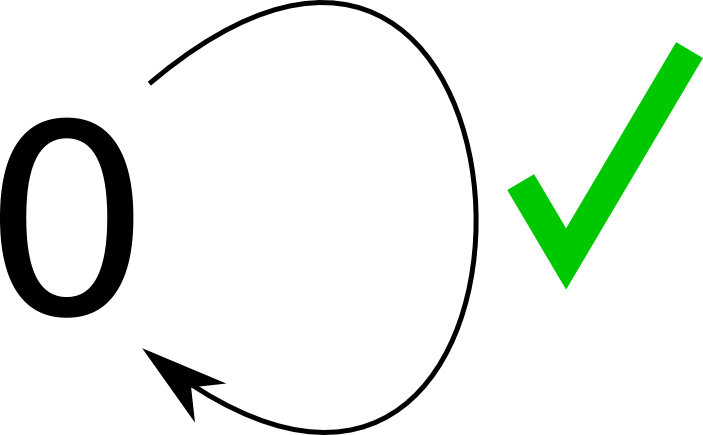

1. Zero is a Number

OK, so \(0\) is a number! Very useful.

Actually, we don’t have to call this \(0\). Let’s call it Peano.

Now Peano is a number! That’s better! Actually, no, it’s exactly the same.

All this Law Of Mathematics says is that there is some number. We haven’t really said what this number does yet. Let’s move on.

2. For every number \(n\), there is a number \(n_S\).

OK, so we know that for every number, there is another number! We have defined here basically the concept of counting. \(n_S\) is the “next number”. Are we done?

Well, no, because I told you that there are 5 Laws Of Mathematics, and we’ve only covered 2.

Also, think about it for a second. Have we really defined counting? Does this definition tell us that we can’t, for example, have \(0_S = 0\)?

No. What it does tell us, however, is that we can’t have two different \(n_S\) for the same \(n\).

3. There is no number \(n\) where \(n_S = 0\)

OK! We dealt with that annoying \(0_S = 0\) problem! We’re done! Well, no… Try to think about a problem with this yourself before you move on.

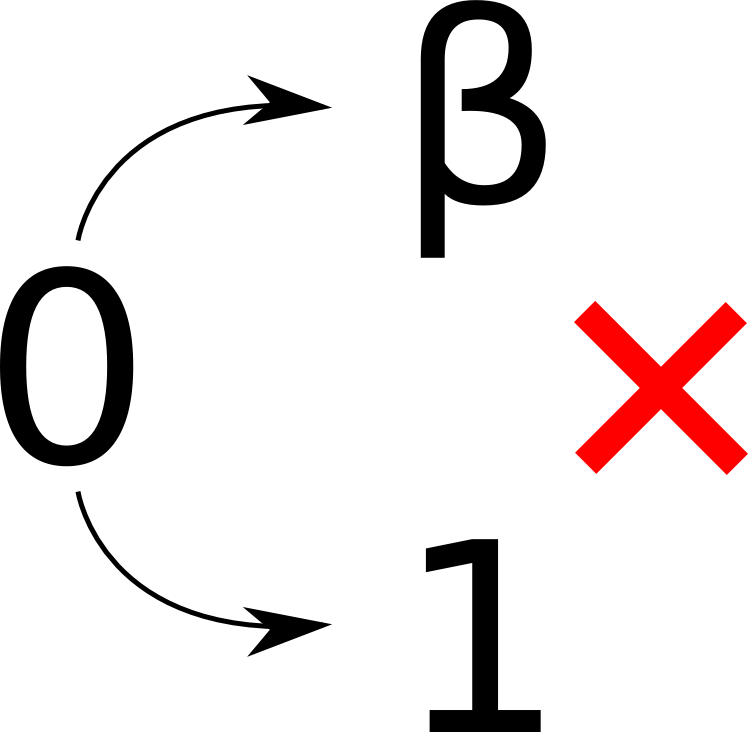

Here it is: Let’s define \(0_S = 1\). Now, is there anything that says that you can’t have \(\beta_S = 1\) where \(\beta \neq 0\)?

Well, no. We have some \(0\) (this follows Law of Mathematics #1). We have, \(0_S = 1\), \(\beta_S = 1\), \(1_S = 2\) (by definition), etc. (this follows Law of Mathematics #2). We have no element \(x\) such that \(x_S = 0\) (this follows Law of Mathematics #3).

Well, we have something that is obviously ridiculous but follows all the Laws. Well, let’s close the loophole!

4. For any two numbers \(x\) and \(y\), if \(x_S = y_S\), \(x = y\)

OK! We’re finally done! No more weird numbers that feed into the regular numbers!

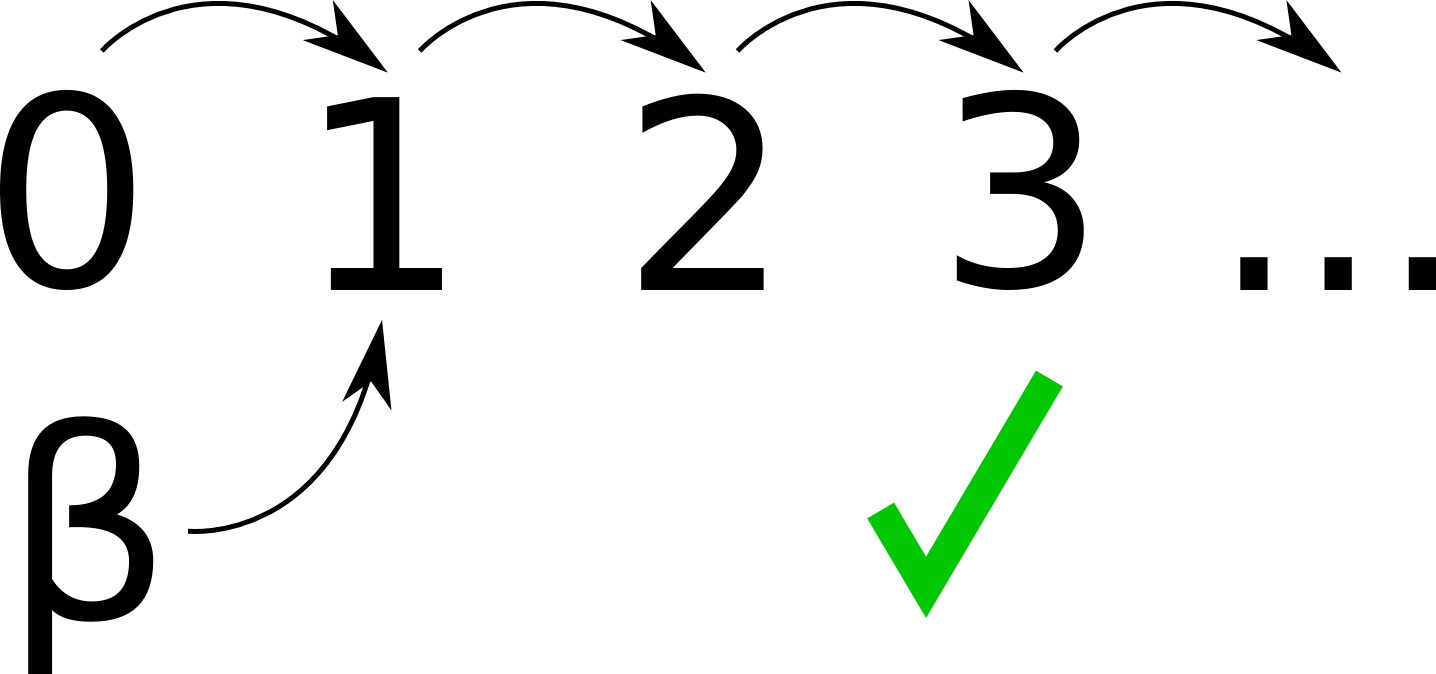

So now let’s define a few numbers:

\[0_S = 1\] \[1_S = 2\] \[2_S = 3\] \[3_S = 4\]

OK, seems to be working. Now let’s define a few more.

\[\gamma_S = \beta\] \[\beta_S = \alpha\]

Where did those annoying Greek letters come from! Well, we’ve said what can be a number: the \(0, 0_S, 0_{SS}, 0_{SSS}\) etc. And we’ve said that no number is before \(0\). And we’ve said that no two numbers can feed into the same number.

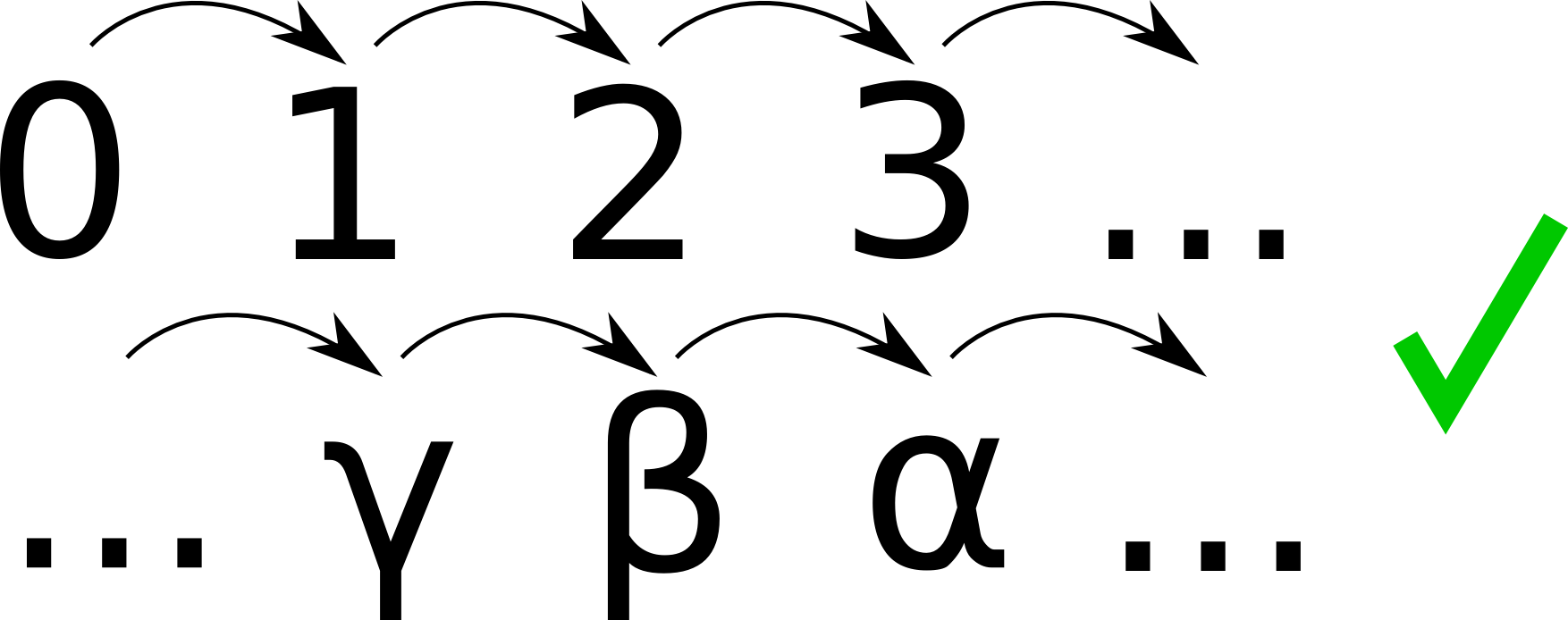

However, what we haven’t said is that the only numbers are \(0, 0_S, 0_{SS}, 0_{SSS}\), etc. And, guess what? That’s the fifth Law!

5. If something is true for \(n = 0\) and its being true for \(n\) makes it true for \(n_S\), then it is true for all numbers.

OK, so this is a little more complicated than the previous examples. But let’s look at a quick example to see how it completes the definition of the numbers. \(\newcommand{\isn}{\uplus}\)

Let’s look at the symbol \(\isn\). Basically, \(x_\isn = \true\), or true when \(x\) is a number, and \(\false\), or false, whenever it is not. (I got the symbol by typing “fancy math symbols” into Google. As far as I know, it isn’t commonly used.)

Some examples:

\[0_\isn = \true\

1_\isn = \true\

2_\isn = \true\

\spadesuit_\isn = \false\

\diamondsuit_\isn = \false\]

As you can see, suits of cards are not numbers, but \(0, 1, 2\) are.

Anyway, the first two axioms can be said as “\(0_\isn\)” and “if \(n_\isn\), then \((n_S)_ \isn\)”

This means that \(n_\isn\) is true for all numbers.

Let that sink in for a minute.

OK, so basically, we proved that all numbers are numbers. But that was just to show that the fifth Law of Mathematics makes sense.

Now for a better example: let’s look at trying to get rid of those annoying Greek Letters. We defined \(\beta\) as some number which isn’t’ the successor of anything in a chain that comes from 0. Let’s define unbetaness as \(n \neq \beta\). We know that \(0 \neq \beta\), and we know that if \(n \neq \beta\) and \(n\) is a number, \(n_S \neq \beta\). Therefore, no number is equal to \(\beta\), so \(\beta\) is not a number.

Now we’re actually done! Well, not really, because we still don’t know what \(2 + 2\) is, since we don’t know what \(+\) means. Let’s look at the Laws of Addition.

1. \(0 + n = n\)

Adding nothing to something doesn’t change it. Not particularly crazy stuff.

2. \(a_S + b = (a + b)_ S\)

Counting up one of the numbers does the same thing as counting up the sum. In other words, if you have two piles, adding a stone to one of the piles is the same as adding a stone to the system as a whole.

So, what is \(2 + 2\)?

\[2 + 2\

1_S + 2\

(1 + 2)_ S\

(0_S + 2)_ S\

((0 + 2)_ S)_ S\

(2_ S)_ S\

3_ S\

4\]

So, you’re wrong, Wikipedia, \(2 + 2\) is not 5!

Anyway, the real point is that while before, you probably thought that \(2 + 2 = 4\) was a basic fact, a Law of Mathematics, now you know that it is just a deduction based on a few other, simpler, laws.