What is Category Theory?

\(\newcommand{\mr}{\mathrm}\) So, I was reading Category Theory for Scientists recently and kept having people ask me: What is category theory? Well, until I hit chapter 3-4, I didn’t really have an answer. But now I do, and I realize that to just understand what it is doesn’t really require understanding how it works.

Sets and functions

So, set theory is all about sets and functions. Why are we talking about set theory and not category theory, you may ask? I’ll get to category theory eventually, but for now, let’s discuss something a little more concrete.

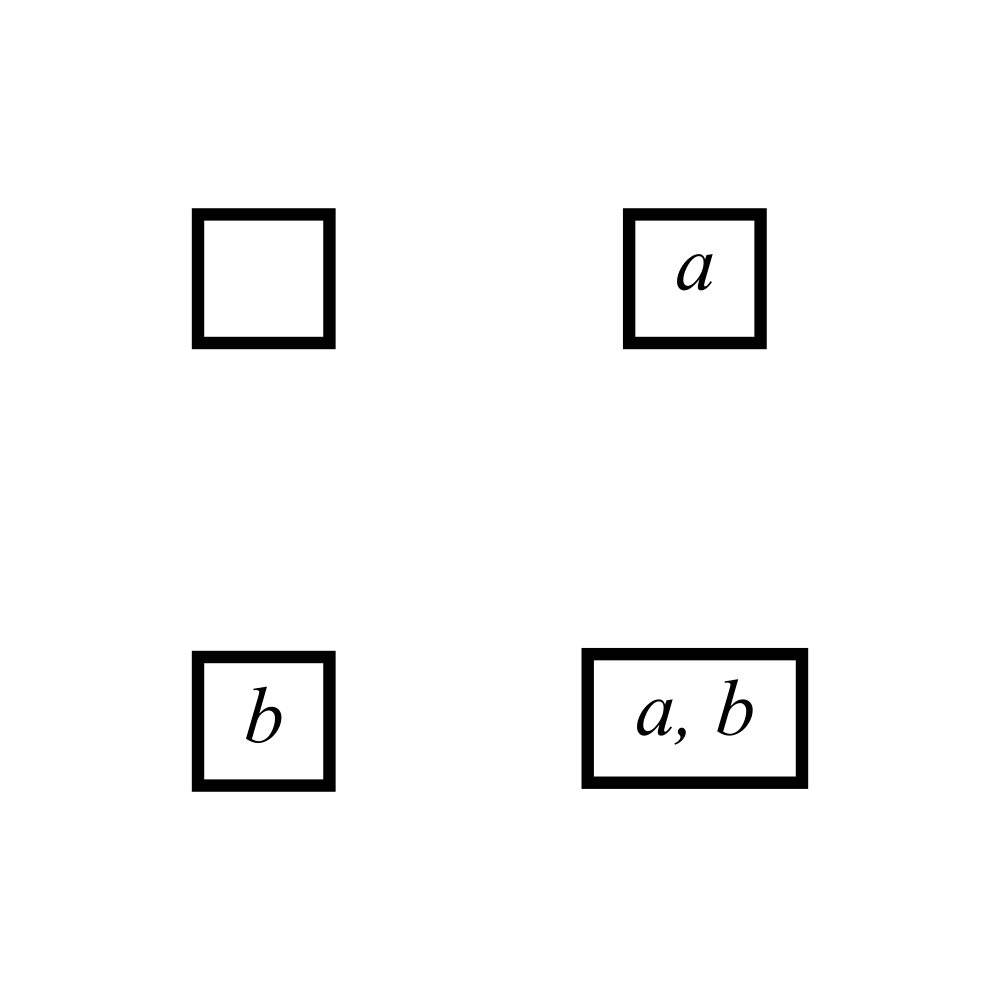

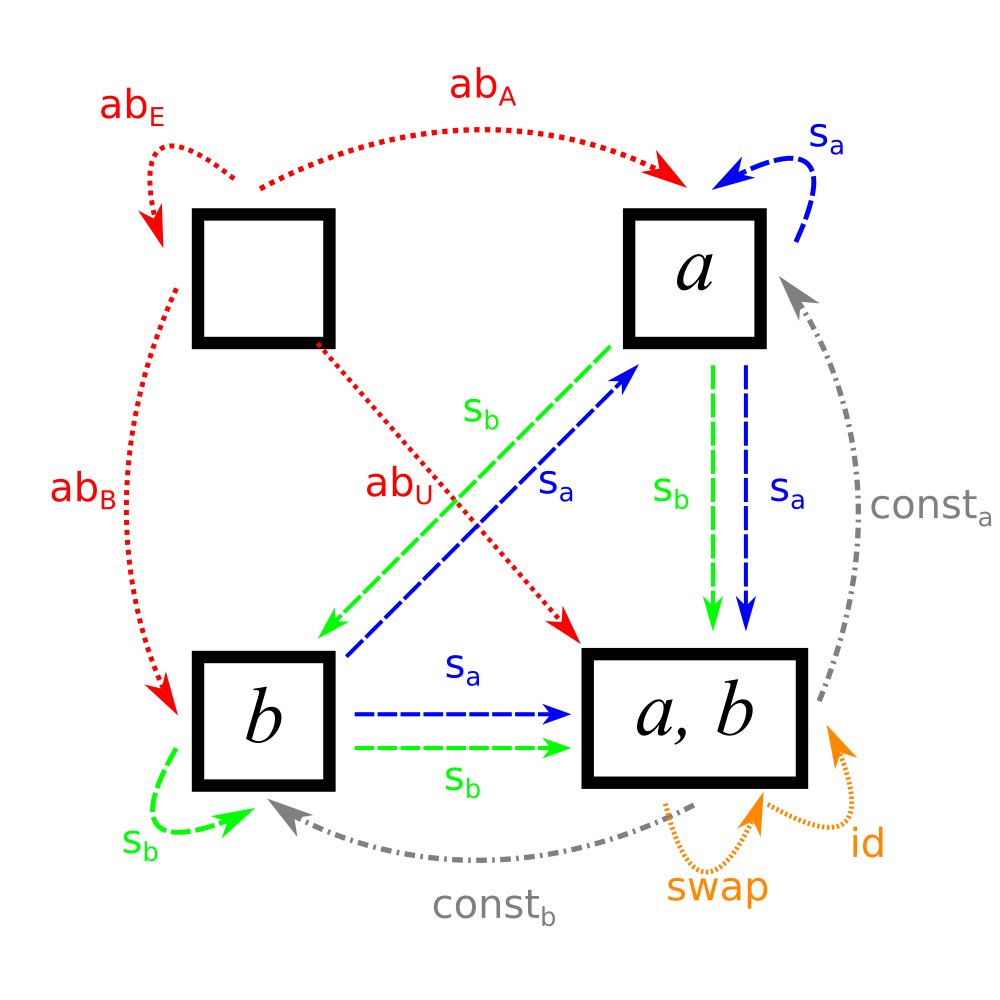

Let’s look at subsets of the set \(\{a, b\}\). We have the possibilities, which we name Empty, A set, B set, Universal set:

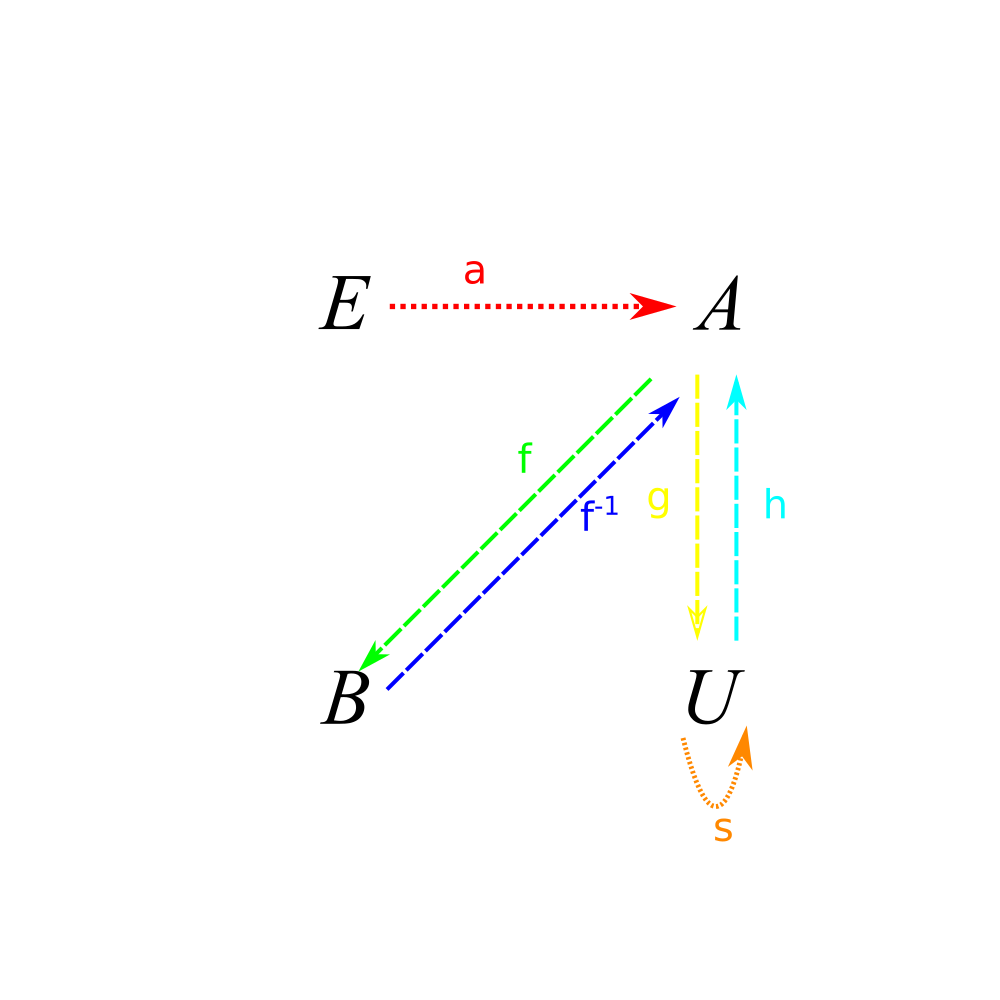

\[E = \{\}, A = \{a\}, B = \{b\}, U = \{a, b\}\]

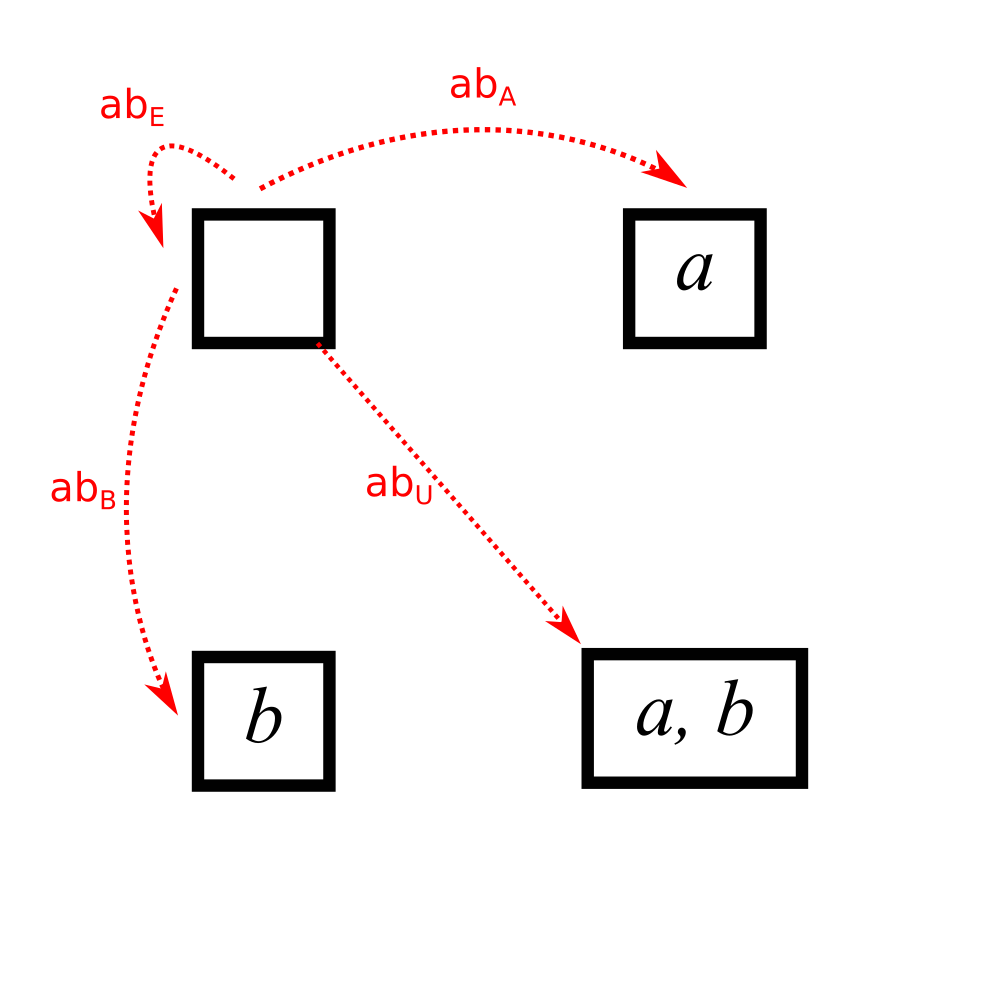

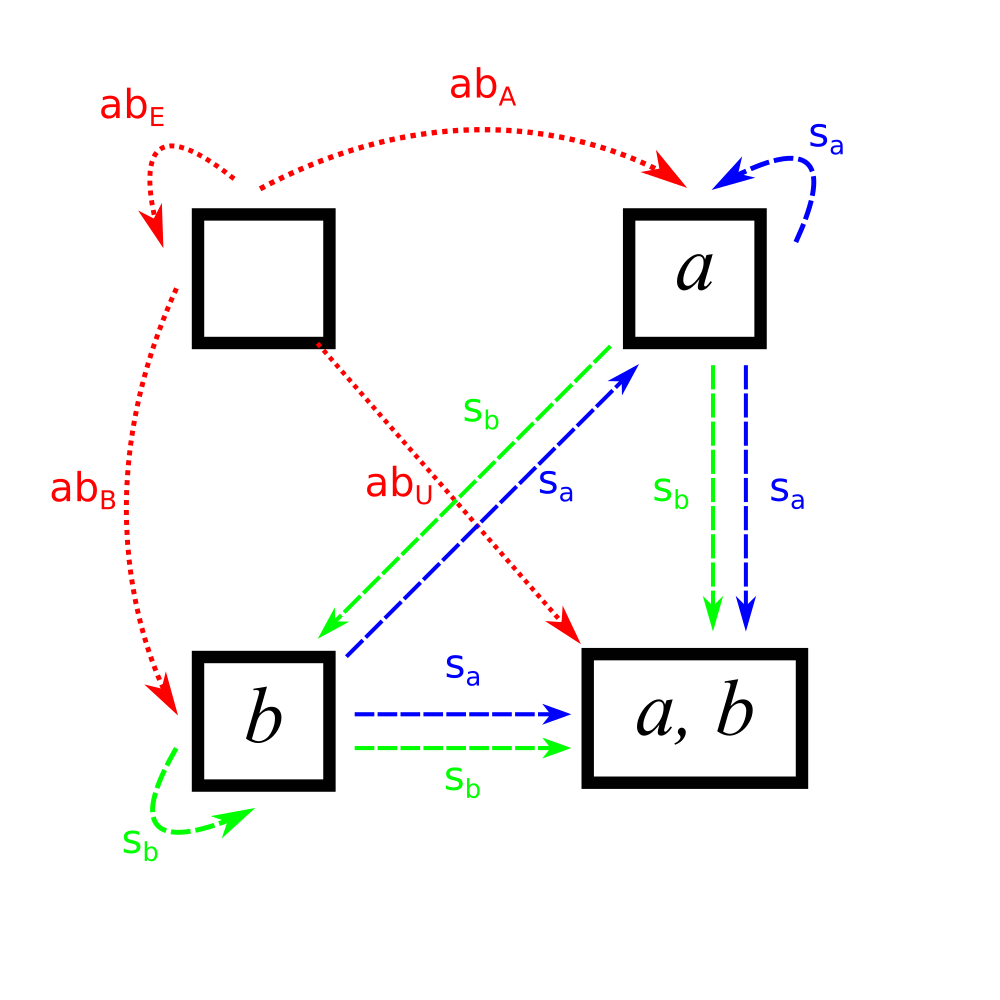

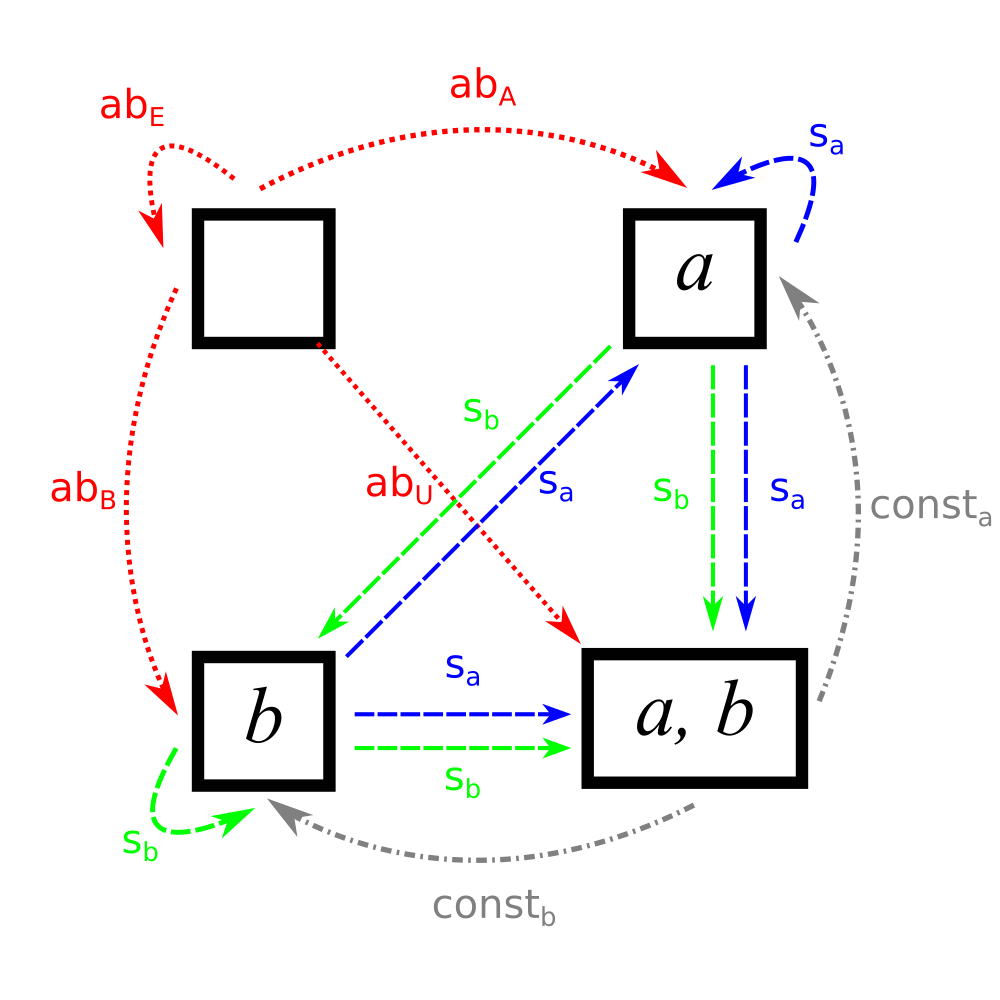

Between \(E\) and any set \(x\), we have the function \(ab_x\), which needs no mappings. (This is called the absurd mapping because if you have to use this function, you are in an absurd situation, a function with no potential arguments).

Now, we can add the functions from the one-element sets \(A\) and \(B\). We know that there is no function to the empty set, since all functions need to have an output for every input. The functions from the one element sets to the other sets are all the constant function \(s_x\) mapping the only element of the domain to the specified element \(x\).

The next step, of course, is finding the functions from \(U\). First, the functions to the one-element sets. These are the functions \(const_x\), which map both elements of \(U\) to \(x\).

Additionally, there are the functions from \(U \rightarrow U\). There are exactly two: the function that preserves identity: \(id\) and the function that swaps \(a\) and \(b\): \(swap\).

Let’s forget elements

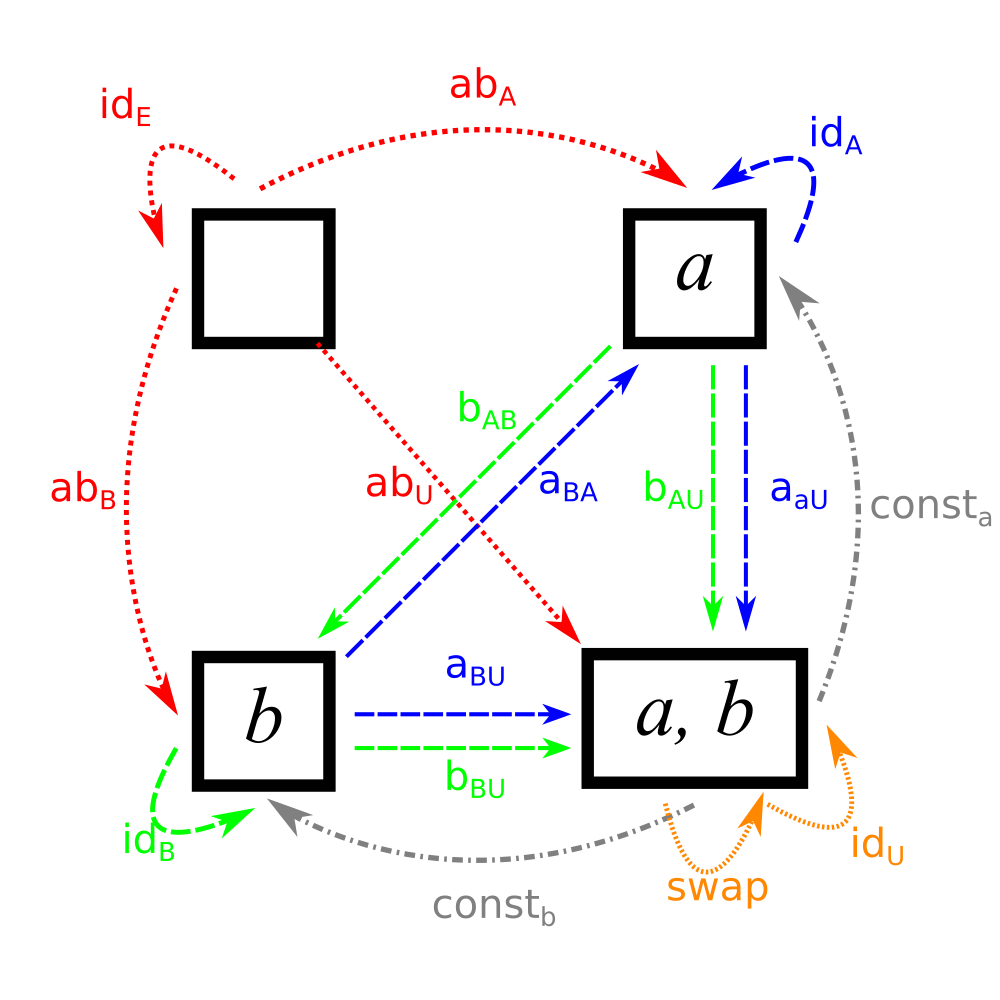

So, we managed to enumerate a bunch of sets and functions between them. For convenience, I’m going to rename all of them to have unique names:

Note the new naming conventions, the arrows from each set to itself are denoted by \(id\), and the functions from set \(E\) to \(F\) that were previously designated \(s_x\) are now designated as the functions \(x_{EF}\) to ensure that no two functions have the same name.

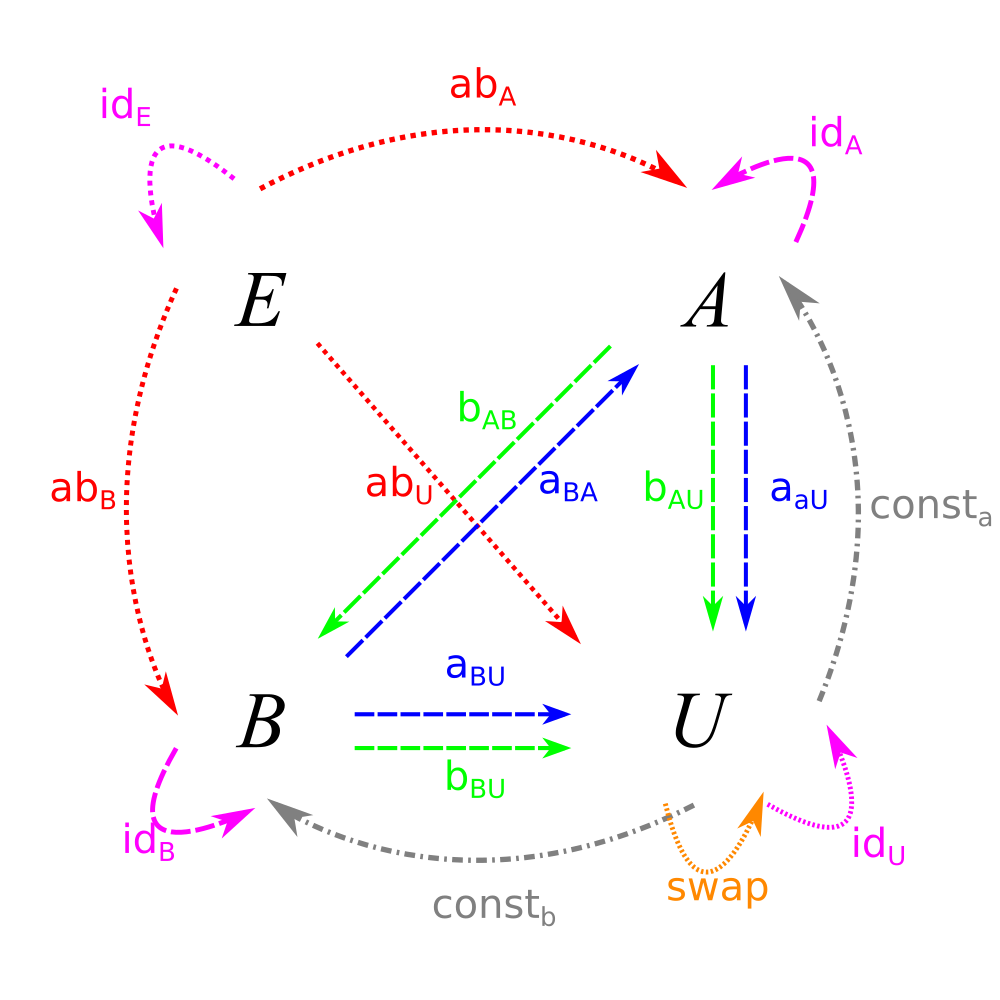

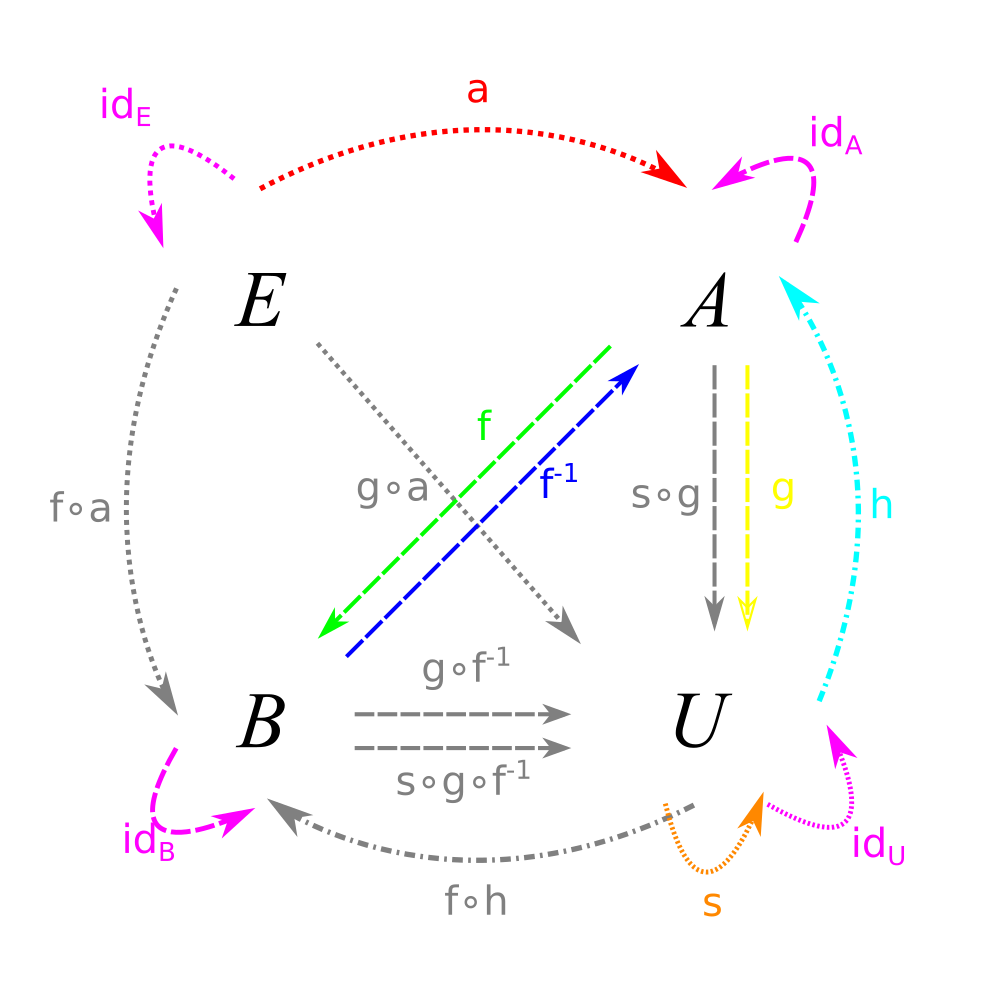

Now, we’re going to do our first transformational move: we’re going to forget the fact that sets contain elements.

Now that we just have a bunch of dots, the labels for the functions seem a little arbitrary. To simplify things, let’s select some functions from which we can get the rest as compositions. Basically, given how simple this system is, we will need to have exactly one function going in and out of every set, along with the swap function, which can’t be defined in terms of constant functions.

In fact, the only functions we need are \((a, f, f^{-1}, g, h, s)\). The rest are compositions. To make this system complete, we need the rules that \(h \circ g = id\) and \(s \circ s = id\).

Anyway, now we don’t need to know what is in the sets at all. Given our amazing composition laws, we can completely describe the network simply in terms of our function arrows!

The category of Sets

OK, so now we have a bunch of dots and arrows between the dots. We now have a category! Basically, category theory is the study of different patterns of these arrows. For an example of the difference between the two fields, look at \(E\). In set theory, the defining factor of \(E\) is that it contains no elements. In category theory, its defining factor is that it contains exactly one arrow to every other set. In fact, it has a special name: the initial object. \(A\) and \(B\) are considered special in set theory because they have one element; in category theory, they are considered special because they have exactly one arrow pointing to them from every other set.

What it’s all about

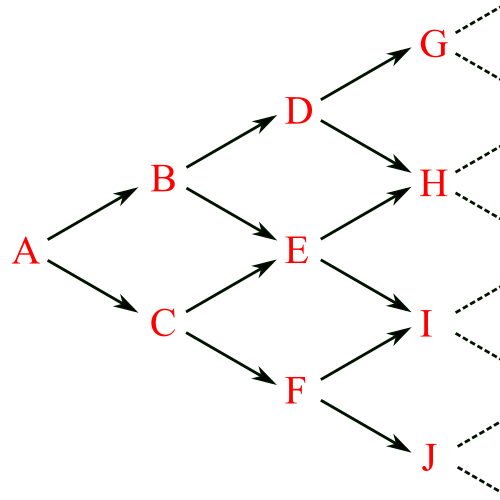

So, category theory is just the study of functions? Well, not exactly. Consider the following directed graph (i.e., a bunch of points with some one-headed arrows connecting the points):

Look familiar? In fact, if you take the paths (i.e., the various ways of getting from point to point) with the laws given above, we end up with the same picture.

Fundamentally, this is what categories are. Any category is basically equivalent to the paths (i.e., ways to get from one letter to another) on some graph. (Actually, there is a way to formalize this in terms of functors, a more advanced concept).

And the power of category theory is that this structure applies to a lot of things.

A lot of categories are basically sets with some limitations on what can be functions between them. For example, Vector Spaces are basically just sets where the only arrows are linear transformation, not just functions.

Other categories are a little more conceptual. e.g., a category that looks like this:

In this category, there are an infinite number of things, with \(n\) in the \(n\)th row, with arrows connecting each thing to two other things. This category is obviously nothing like that of sets. However, we can still see that \(A\) is an initial object, like the empty set in the category of sets.

Conclusion

The really fun part of category theory actually has to do with functions between categories called “functors”. Then there is a category of categories where the arrows are the functors and the objects are the categories. And then they add like 20 levels of abstraction until your head hurts.

But at its base, category theory is just the study of paths on graphs, the way that set theory is the study of unique elements of lists. Nothing too intimidating, and it does generalize a lot of theorems about things.