Monoids, Bioids, and Beyond

Two View of Monoids.

Monoids

Monoids are defined in Haskell as follows:

class Monoid a where

m_id :: a

(++) :: a -> a -> a

Monoids define some operation with identity (here called m_id). We can define

the required laws, identity, and associativity, as follows:

monoidLaw1, monoidLaw2 :: (Monoid a, Eq a) => a -> Bool

monoidLaw1 x = x ++ m_id == x

monoidLaw2 x = m_id ++ x == x

monoidLaw3 :: (Monoid a, Eq a) => a -> a -> a -> Bool

monoidLaw3 x y z = (x ++ y) ++ z == x ++ (y ++ z)

Morphisms

Now, I’ll introduce something else:

class (Morphism f) where

id :: f x x

(.) :: f b c -> f a b -> f a c

Morphisms also have laws:

morphismLaw1, morphismLaw2 :: (Morphism f, Eq (f a b)) => f a b -> Bool

morphismLaw1 f = f . id == f

morphismLaw2 f = id . f == f

morphismLaw3 :: (Morphism f, Eq (f a d)) => f c d -> f b c -> f a b -> Bool

morphismLaw3 f g h = (f . g) . h == f . (g . h)

This definition defines a morphism, or a generalization of a function, in the category of Haskell types.

We can make things instances of morphisms as such:

instance (Morphism (->)) where

id x = x

(f . g) x = f (g x)

Morphisms and Monoids

Note that while a Monoid is a concrete type, a Morphism is a higher-order-type that takes two types as inputs. However, apart from this, we have fairly similar set of given functions with a similar set of laws.

To make the comparison explicit, we can look at endomorphisms, that is morphisms from a set to itself.

data Endo morph set = Endo (morph set set)

instance (Morphism morph) => (Monoid (Endo morph set)) where

m_id = Endo id

Endo f ++ Endo g = Endo (f . g)

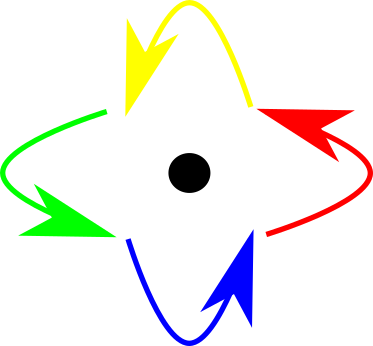

So, we can see that monoids can be viewed as morphisms from a set to itself. Here is a diagram of that. The elements of the monoid are the arrows.

In any case, we now have a new way of expressing a monoid: as a set of morphisms from a set to itself.

Bioids

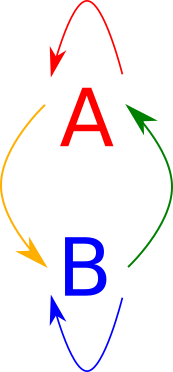

We can define a bioid to be the arrows between two objects. These fall into four different sets, those from \(A \to A\), those from \(A \to B\), those from \(B \to A\), and those from \(B \to B\). This can be represented diagrammatically as follows:

If we want to enforce the laws of the category, we know that we need to enforce a monad structure on both \(A\) and \(B\). We also know that we must have four additional composition values. In Haskell syntax, we have:

class (Monoid aa, Monoid bb) => Bioid aa bb ab ba

| aa -> ab, aa -> ba, bb -> ab, bb -> ba, ab -> aa, ab -> bb, ba -> aa, ba -> bb, aa -> bb, bb -> aa, ab -> ba, ba -> ab where

id_a :: aa

id_b :: bb

(%%) :: ab -> ba -> aa

(^^) :: ba -> ab -> bb

(#>) :: ab -> aa -> ab

(<#) :: aa -> ba -> ba

($>) :: bb -> ab -> ab

(<$) :: ba -> bb -> ba

OK, I don’t want to write down the laws for that mess. I now understand why mathematicians stopped at monoids but not bioids. To be completely honest, I was hoping to get semirings out of this mess, but I don’t think it’s actually possible.

And Beyond

In any case, we can still notice something interesting about a Bioid. It has a total of eight composition rules, if you include the two monoid rules. How can we calculate this number in general?

First, let’s define an n-oid as the morphisms on a category with \(n\) objects. We know that there are \(n^2\) types of morphisms (\(n\) sources and \(n\) destinations). We also know that each composition rule contains three types in any order:

\(\circ :: m b c \to m a b \to m b c\)

So there are therefore \(n^3\) ++ equivalents on an n-oid. Yeah, in general that’s going to get messy very fast.