How You Get Homeopathy

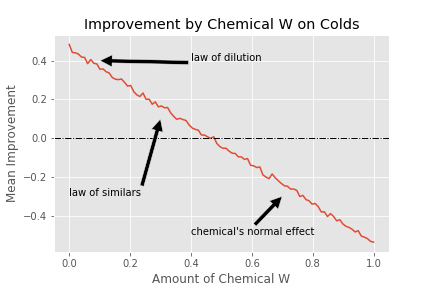

Homeopathy is a system that has two primary claims. The first is the law of similars. It says that a dilute solution of a substance cures the ailment caused by a concentrated solution of the same substance. The second is the law of dilution, which says that the more dilute a homeopathic preparation is, the stronger its effect.

The second theory is the one people tend to focus on because it is clearly incorrect. The anti-homeopathy \(10^{23}\) campaign is named after the order of magnitude of Avogadro’s number, that is the number of molecules of a substance in a 1M solution of a substance (typically a fairly strong solution, 1M saltwater is 5 teaspoons of salt in a liter of water). If you dilute by more than that amount, and many “strong” homeopathic preparations do, then with high probability you literally have 0 molecules of the active ingredient in your preparation. As the \(10^{23}\) campaign’s slogan makes clear, “There’s nothing in it” and homeopathic medicines are just sugar pills.

How do you get here?

One of the questions I had when I first heard of homeopathy is how do you even come up with this system? Other systems of alternative medicine tend to involve things that probably started out as offshoots of relaxing activities (such as acupuncture, reflexology, chiropractic, etc. which all bear some resemblance to massage), herbs (many of which do have effects and have been incorporated into real medicine, with the remainder being relegated to alternative medicine), or situations in which you can fool yourself by making vague predictions that turn out to be true for a lot of people but feel individualized (psychics, tarot, astrology, etc.).

But homeopathy just kinda looks like medicine. Its preparations need to be made with a complicated procedure, scientific calculations are involved, and it isn’t ancient, only dating back to the 18th century. It’s basically medicine except that its central premises make no sense and it doesn’t stand up to empirical scrutiny. (As you might expect, comparing homeopathic sugar pills to regular sugar pills in a trial shows no difference.)

Well, this is a math and CS blog mostly, not a skeptical rant blog, so I’ll walk through one theory I have on why the claims of homeopathy could seem convincing to its earliest practitioners.

A model of a disease

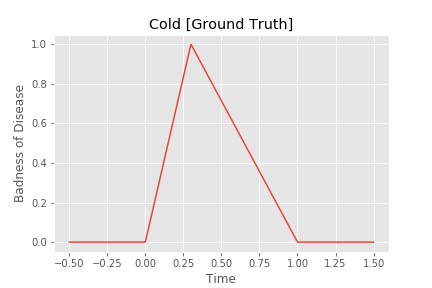

Let’s take a disease that starts out ok, then gets worse rapidly, then gets better slowly (like a cold). We can model it as such:

Obviously this is simplified but hopefully it matches your intuition about how many diseases work.

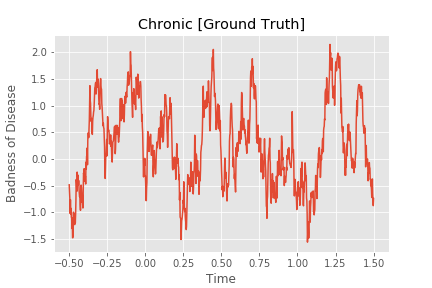

Let’s now take a chronic disease that changes more or less randomly with time. Specifically, it is a blurred version of a series of independent standard normal samples.

Now that we have a few disease models, lets look at when you might seek treatment.

A model of times when you seek treatment

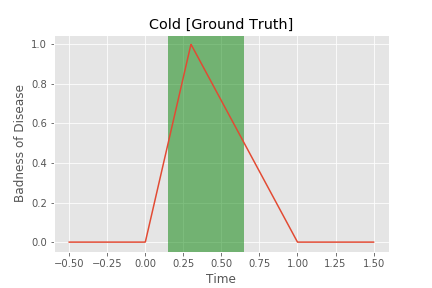

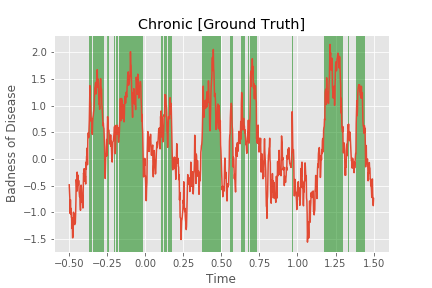

Generally, you seek treatment only when your disease gets bad. You usually won’t start treatment on a cold if you’re doing OK and you won’t start treating your seasonal allergies unless you’re having a bad day. Let’s say that you seek treatment when your disease is greater than 0.5 badness units. On the charts we saw before, we now have the following ranges:

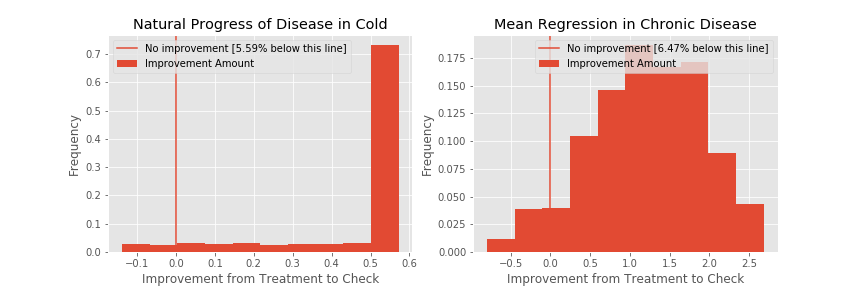

If we get treatment during one of these times and then check back with how your condition is in 0.2 time units (for example), you get improvements as such:

Note that the mean of both of these distributions is higher than 0. In the case of the cold, this effect is called natural progress of the disease, and it refers to how the disease will get better with or without treatment from its worst point, which occurs towards the middle. In the case of a chronic disease this effect is called mean reversion. If your disease randomly has good or bad days, the disease is equally likely to go to any state after a bad day. Since most states are better than a bad day, the disease will generally get better after a bad day.

Treatments

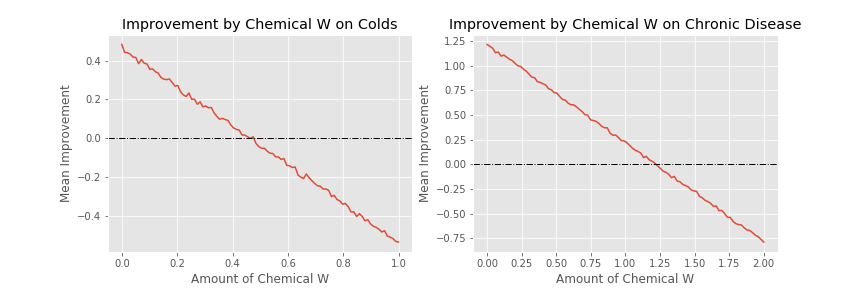

Let’s say you find a chemical that makes a disease worse (let’s call it chemical W). For simplicty’s sake, let’s say that 1 unit of W leads to 1 unit of worsening of the condition, with some noise. Taking a dosage response curve, we get the mean improvement numbers as such:

Looking more closely at the cold graph (since both show the same general effect), we can see both the principles of homeopathy!

Of course, this analysis assumes that you’d expect no improvement. In the case of a cold, that seems like a silly expectation. Of course colds cure themselves, right? But in the case of chronic conditions (to take a relatively benign example, seasonal allergies) this isn’t necessarily the assumption people have, they think that their disease is equally likely to get better or worse the next day implicitly. Even in the case of a cold, if you’re doing a study without a control its easy to see the improvement in the effect for your treatment and assume that its working without thinking through the statistical biases at play.

Further Questions

This mistake leads you to see a smaller amount of harm as a benefit. However, I still don’t really know where the logarithmic view of homeopathy comes from, where \(10^{-10}\) of a substance is viewed as half as potent as \(10^{-20}\) of the substance, when this model would lead you to conclude that they are equally potent. I suspect that confirmation bias might play a role as well.

Anyway, for me this was yet another point in favor of the good ol’ Randomized Control Trial! You can try to create a complicated model like this for every possible weird statistical effect, or you can account for all of them with a control wing, and ensure that you don’t fool yourself.