A Monadic Model for Set Theory, Part 1

\(\newcommand{\fcd}{\leadsto}\)

Solving an Equation

A lot of elementary algebra involves solving equations. Generally, mathematicians seek solutions to equations of the form

\[f(x) = b\]

The solution that most mathematicians come up with to this problem is to define left and right inverses: The left inverse of a function \(f\) is a function \(g\) such that \(g \circ f = \mathrm {id}\). This inverse applies to any function that is one-to-one. There is also a right inverse, a function \(g\) such that \(f \circ g = \mathrm {id}\) For example, the left inverse of the function

\[x \mapsto \sqrt x :: \mathbb R^+ \rightarrow \mathbb R\]

is the function

\[x \mapsto x^2 :: \mathbb R \rightarrow \mathbb R^+\]

Because

\[(\sqrt x)^2 = x\]

On the other hand,

\[\sqrt {x^2} = |x| \not\equiv x \]

so it is not a right inverse.

Of course, this is a very function-oriented way of looking at the problem. Nothing wrong with that, of course, it actually generalizes pretty well, but it can sometimes seem like it’s getting in the way.

For example, solving \(|x| = 2\) can’t be done using functions. We instead need to use funcads.

Funcads

Funcads are a generalization of functions. A funcad from \(A\) to \(B\) is defined as a function mapping from elements of \(A\) to subsets of \(B\).

\[A \fcd B \equiv A \to \mathbb P(B)\]

\(x \mapsto \{-x, x\}\) is an example of a funcad.

The usefulness of funcads is in large part from the way in which they are isomorphic to relations. A relation \(A \succ B\) is a subset of \(A \times B\), e.g., a set of ordered pairs of elements of \(A\) and \(B\).

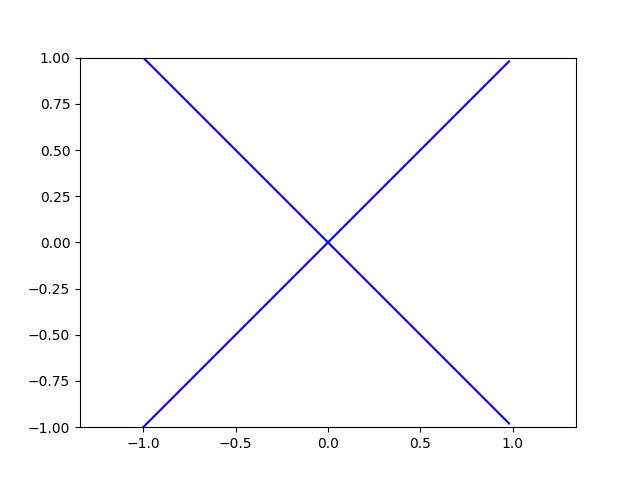

Relations of type \(\mathbb R \succ \mathbb R\), can be represented as graphs in the plane. For example, the example above can be represented as what looks like the union of the plots of two functions.

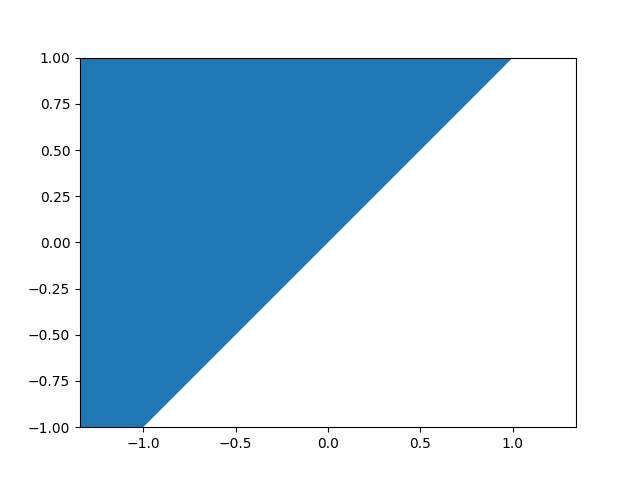

A less function-like example is the relation \(\{(x, y) | x < y\}\).

In this case, we can define a funcad \(x \mapsto \{y | x < y\}\).

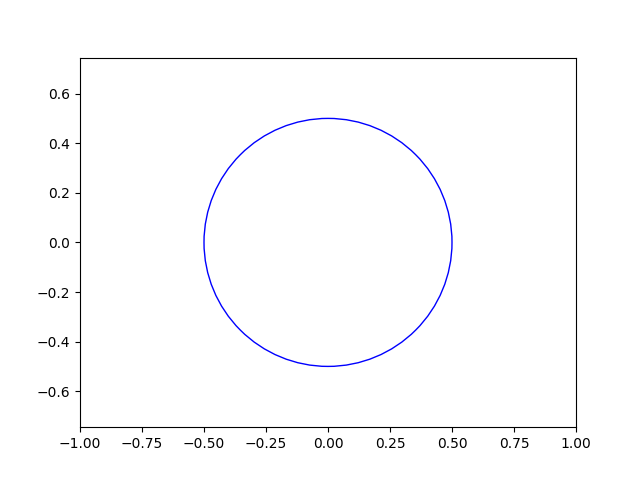

Another example is the relation \(\{(x, y) | x^2 + y^2 = 1\}\)

This relation can be represented by the relation

\[x \mapsto \left\{\begin{array}{rl}

\{\sqrt{1-x^2}, -\sqrt{1-x^2}\} & \mbox{if }-1\leq x \leq 1\

\{\} & \mbox{otherwise}

\end{array}\right.\]

In general, any relation

\[\{(x, y) | \phi(x,y)\}\]

can be represented as the funcad

\[x \mapsto \{y | \phi(x,y)\}\]

And any funcad

\[x \mapsto f(x)\]

can be represented as the relation

\[\bigcup_{\forall x \in X} \{(x,y) | y \in f(x)\}\]

A taxonomy of Funcads

If funcads are just another way to express relations, then why do they matter? In reality, funcads are a convenient way of looking at relations from a function-oriented perspective. There is an input, and a set of possible outputs. Of course, there are many ways to classify funcads, but as a primer, you can look at this convenient chart:

| Input | Output | |

| Hits everything | Total | Surjective |

| Only one for each | Functional | Injective |

The second column should seem familiar if you’ve taken Linear Algebra or Set theory (you might know the terms onto and one-to-one rather than surjective and injective). On the other hand, when dealing with functions, we don’t normally have to worry about totality or functionality.

Total Funcads

A total funcad is one that assigns at least one value to every input:

\[f :: X \fcd Y \implies (\forall x \in X)(|f(x)| \geq 1)\]

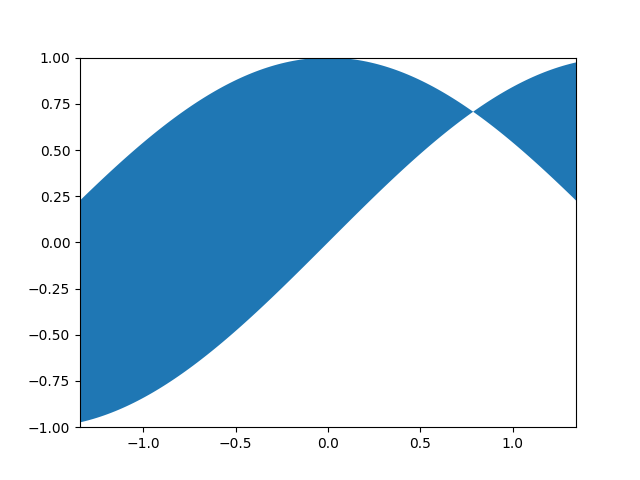

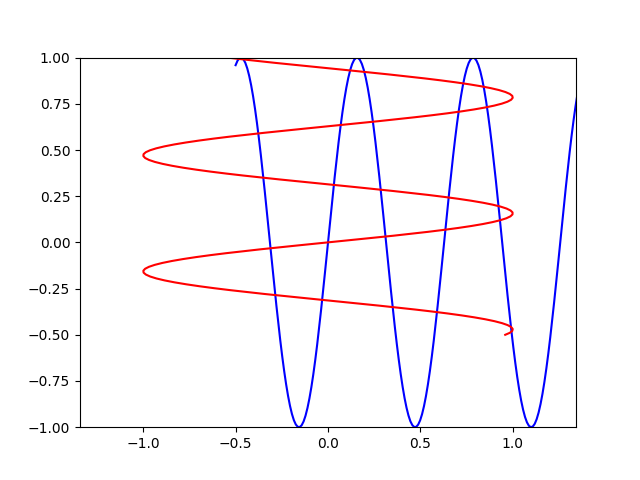

An example of a total funcad is \(<\) (see above). Another example is the funcad \(x \mapsto \{y | \min(\sin x, \cos x) \leq y \leq \max(\sin x, \cos x)\}\):

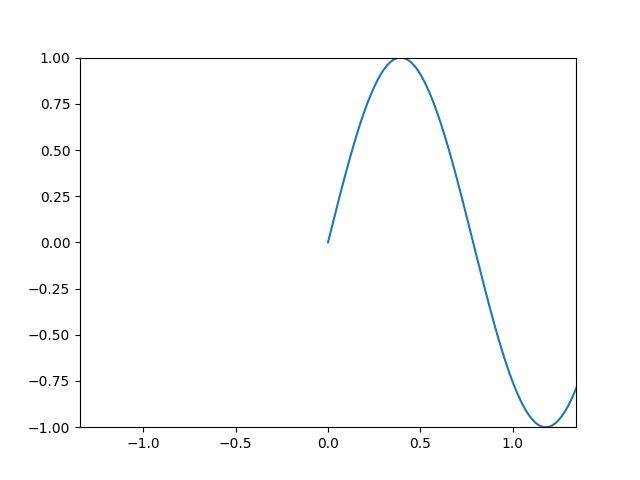

As you can see, to every \(x\) value there is associated at least one \(y\) value. This is a particularly pathological example because it doesn’t fall into any of the other categories.

Functional funcads

A functional funcad is one that assigns at most one value to every input:

\[f :: X \fcd Y \implies (\forall x \in X)(|f(x)| \leq 1)\]

Such funcads are called “functional” because they can be considered functions from the set of points that they have a value for to the original output set.

\[f :: X \fcd Y \wedge f \mbox{ functional} \implies f :: \{x \in X | |f(x)| = 1\} \to Y \]

Additionally, every regular function \(X \to Y\) is a functional and total funcad \(X \fcd Y\).

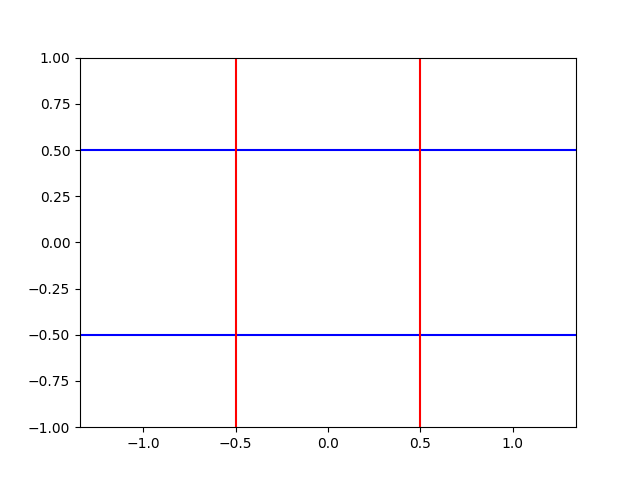

An example of a functional funcad is \(x \mapsto \left\{\begin{array}{rl}\{\sin{4x}\}&\mbox{if } x \geq 0\\ \{\} &\mbox{otherwise}\end{array}\right.\)

Surjective funcads

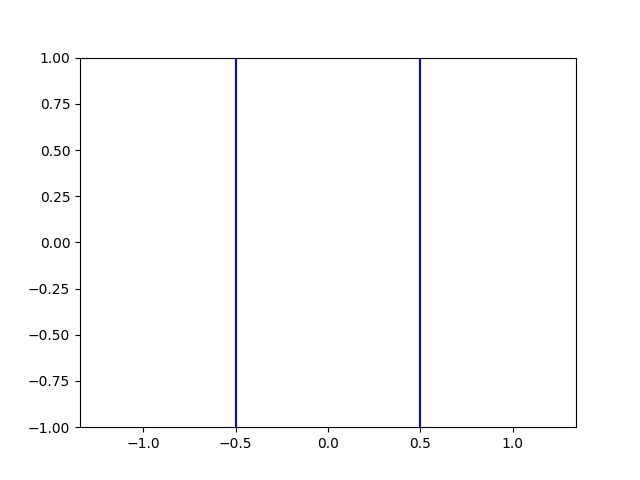

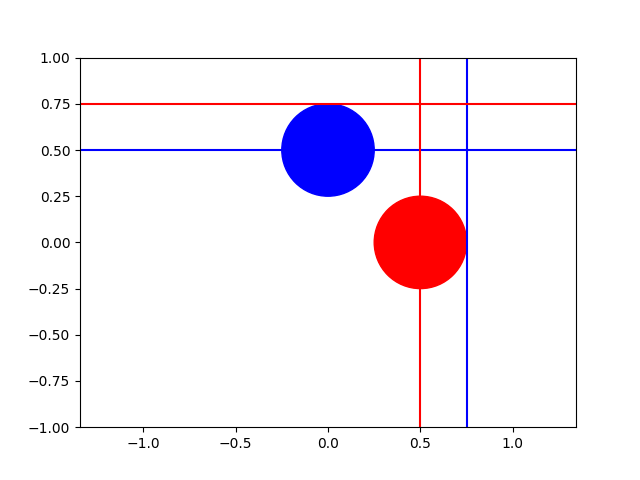

An onto funcad is one that “hits” each value \(y\). For example, \(x = \pm \frac 1 2\):

Injective funcads

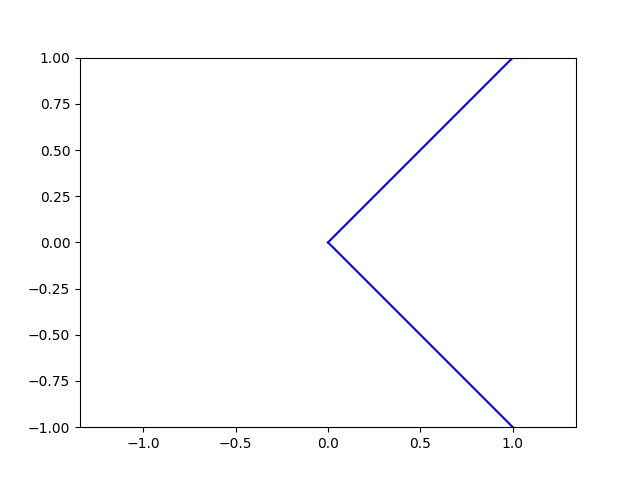

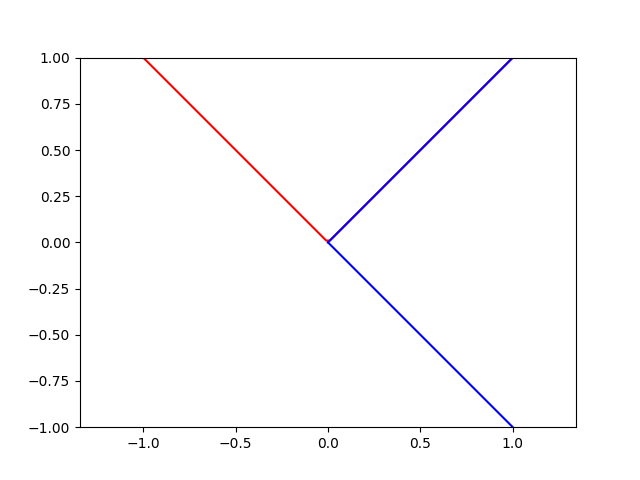

An injective funcad is one that has at most one value \(y\) for each value \(x\). For example, \(y = \pm x, x > 0\)

Inverse funcads

OK, so a taxonomy is nice and all, but how does this help us? Well, it turns out that this taxonomy ends up working pretty well with the concept of an inverse.

The inverse of a funcad is defined as the funcad that produces the relation with \(x\) and \(y\) flipped.

In other words,

\(f^{-1} (y) = \{x \in X | y \in f(x)\}\)

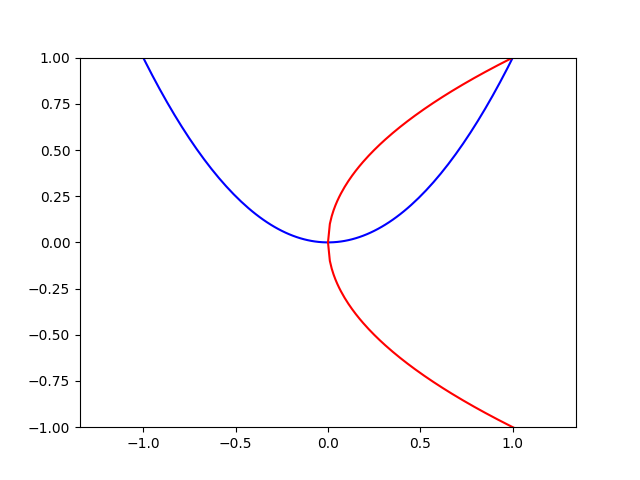

Some funcads (blue), and their inverses (red), are shown below.

Square

Abs

Some Random Relation

Classification of Inverses

So, if we have a total funcad, what can we say about its inverse?

Well, here’s a total funcad and its inverse.

As you can see, the funcad’s inverse is surjective. Similarly, a surjective funcad’s inverse will be injective.

Similarly, it becomes fairly simple to prove that the inverse of any functional funcad will be injective. Here is an example:

To be continued

OK, so I just realized that this post ended up being longer than I expected. Next time on “On Error Resume Prior”: compositions and solving some actual problems!