Voting is Rational

A common refrain in politics-adjacent discourse is “why bother voting? there’s no chance your individual vote will affect the outcome of the election!” This concept is often conceptualized in political science as the Paradox of Voting. However, with a few simple assumptions, the paradox disappears.

Yes, voting is unlikely to directly change the outcome,

Assume there’s v voters and the election is predicted to have a margin of \(x \pm y\) points. We can model the predicted margin as a normal distribution (usually a reasonable assumption) and then stretch this out by \(v\) to give a distribution of raw vote margins.

We then can use the height of this probability distribution at 0 (a tied vote) to roughly model the probability of a single voter swinging the election.

This turns out to be relatively easy to compute, and is given by the formula

\[h = \frac{1}{vy\sqrt{2\pi}} * \exp\left(-\frac 12 \left(\frac{x}{y}\right)^2\right)\]This is often a very small value! For example, if you consider a typical election with 5 million voters in a close state, where the polling average is expected to be D+2, with a standard deviation polling error of 6 points, this ends up being 1 in 840,000!

So it’s easy to see why people think voting is irrational is irrational, as there is a very small chance you affect the result.

But the payoff to swinging an election is huge

However, it’s important to remember that if you’re deciding an election, you’re deciding the fate of every single person in the region of interest! This means that if you put a value of \(k\) on the average person’s quality of life improvement, and there’s n people in this society, the value of swinging an election is \(kn\). If we then express the number of voters in this society as \(v = nt\), where \(t\) is “turnout” (here defined as the percentage of people who vote), then we have that our formula becomes

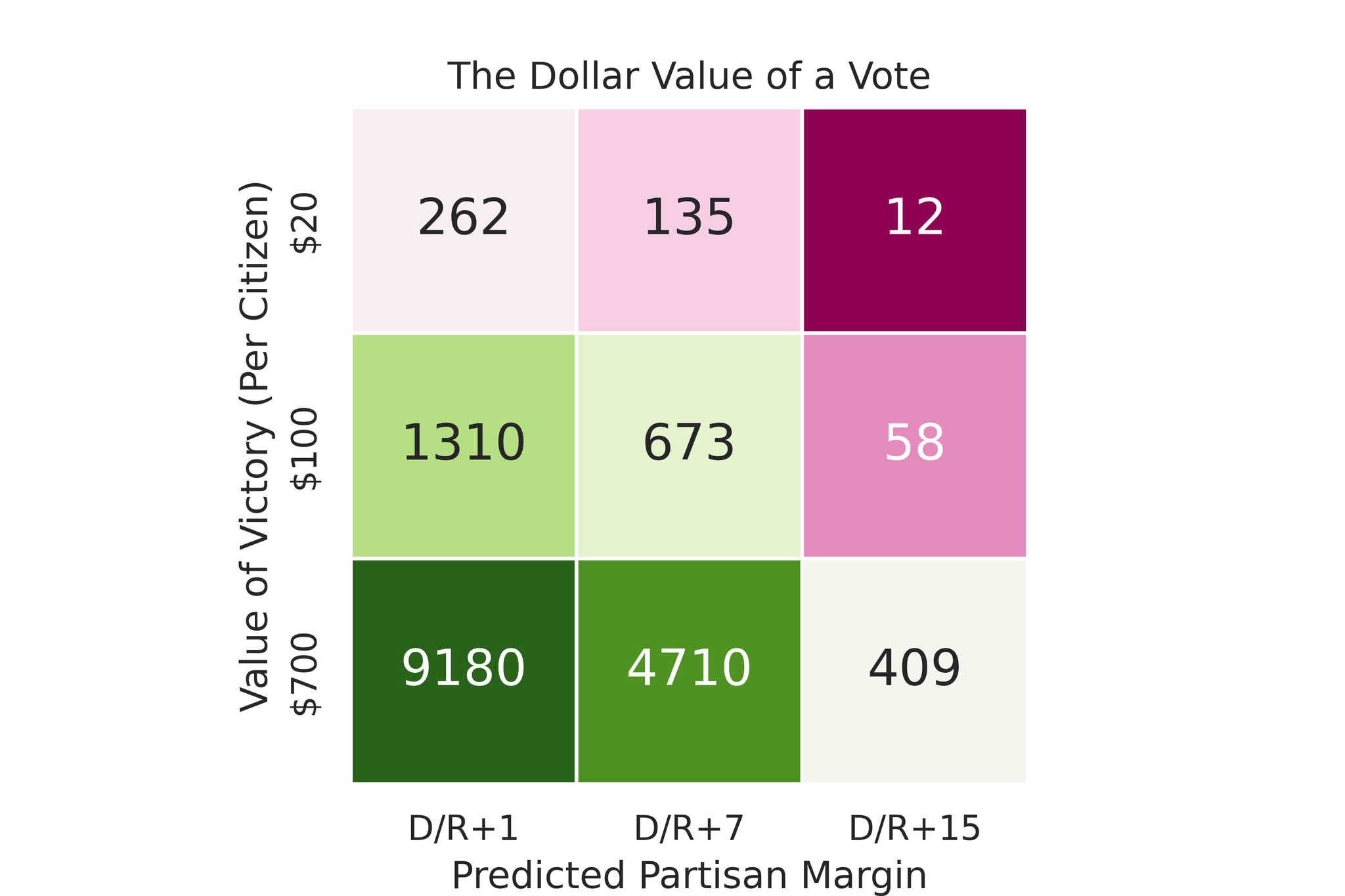

\[h = k\frac{1}{ty\sqrt{2\pi}} * \exp\left(-\frac 12 \left(\frac{x}{y}\right)^2\right)\]This lets us assign a dollar value to a marginal vote – that is to say, how much value should be assigned to persuading a single voter to vote before the election? Let’s take Georgia’s 2021 election, where Democrats campaigned on $1,400 checks for the populace (on average ~$700 per resident, as not all people got checks). In this case, with a predicted margin of D+1, the expected value of a marginal vote for the Democrats would actually be E = $9180 – each additional voter that they activate on top of the regular electorate would be worth $9180 to the state’s populace, based on the disbursement predicated on a Democratic victory. The below table highlights several other scenarios and how much a vote would be worth in each of those

In other words, if voting is affordable and accessible, you should absolutely vote if you care about other people in society. Given how easy it generally is to vote (at most a few hours of time are spent), it is well worthwhile in almost all cases.

Caveats

The first caveat here is that we are assuming that a rational voter should care about other people in society. I think this is where the paradox of voting crowd would most take issue. However, we think it is reasonable to assert that a rational actor in a society should apply a universal perspective, otherwise more or less all forms of political action, from signing up to a union to following laws that are hard to enforce would be nullified.

Now of course, the value of a vote varies a lot depending on the circumstance. If, for example, you don’t have a competitive election (say, Tennessee, where the presidential outcome is predicted to be R+25), the value of a presidential vote is virtually zero, because your individual odds of changing the outcome are next to none, even once multiplied by the population. Here, the value of voting is probably not that useful, though in almost all cases, there’s other, closer elections on the ballot that are absolutely worth voting in. In short, voting is important!